Popular music has a close connection with the recording studios where it was born: The Beatles - unthinkable without Abbey Road Studios in London. The typical sound of the 1990s boy bands was created in Sweden’s Cheiron Studios. And without the Jamaican sound labs of King Tubby and Lee “Scratch” Perry there would have been no dub.

In the same vein, the CAN studio played a key role - not only for the music of the eponymous band, but also in German and international pop music. The atmosphere, acoustics, special technical equipment and personalities of the performers all left their mark on the music that was created there.

In 1971 CAN moved from their rehearsal rooms in Nörvenich Castle to a defunct movie theatre in the community of Weilerswist. Having been earning money with movie scores they were now seeking a creative space of their own.

The band members were Irmin Schmidt, Jaki Liebzeit, Holger Czukay and Michael Karoli. While Malcolm Mooney and Damo Suzuki were the most prolific of their changing lead vocalists. Some of the band members had studied with Karl-Heinz Stockhausen, who had caused a sensation with his studio experiments at that time. Now they broke new ground in rock music themselves: They exchanged instruments, sought inspiration in non-European music, and always taped their jams, only to later re-edit parts of the recordings.

Wanting to rehearse day and night, they covered the studio walls with old army mattresses. This screened them from the outside world so as not to annoy their neighbours. As a welcome side effect, this produced a “dry” sound, leaving little ambient noise on the recordings. Nevertheless, the band made a point of recording the “atmosphere” as well: creaking chairs and sounds from the garden. They decorated the mattresses with bright, psychedelic scarves, and there were seating areas and couches to sit down on everywhere.

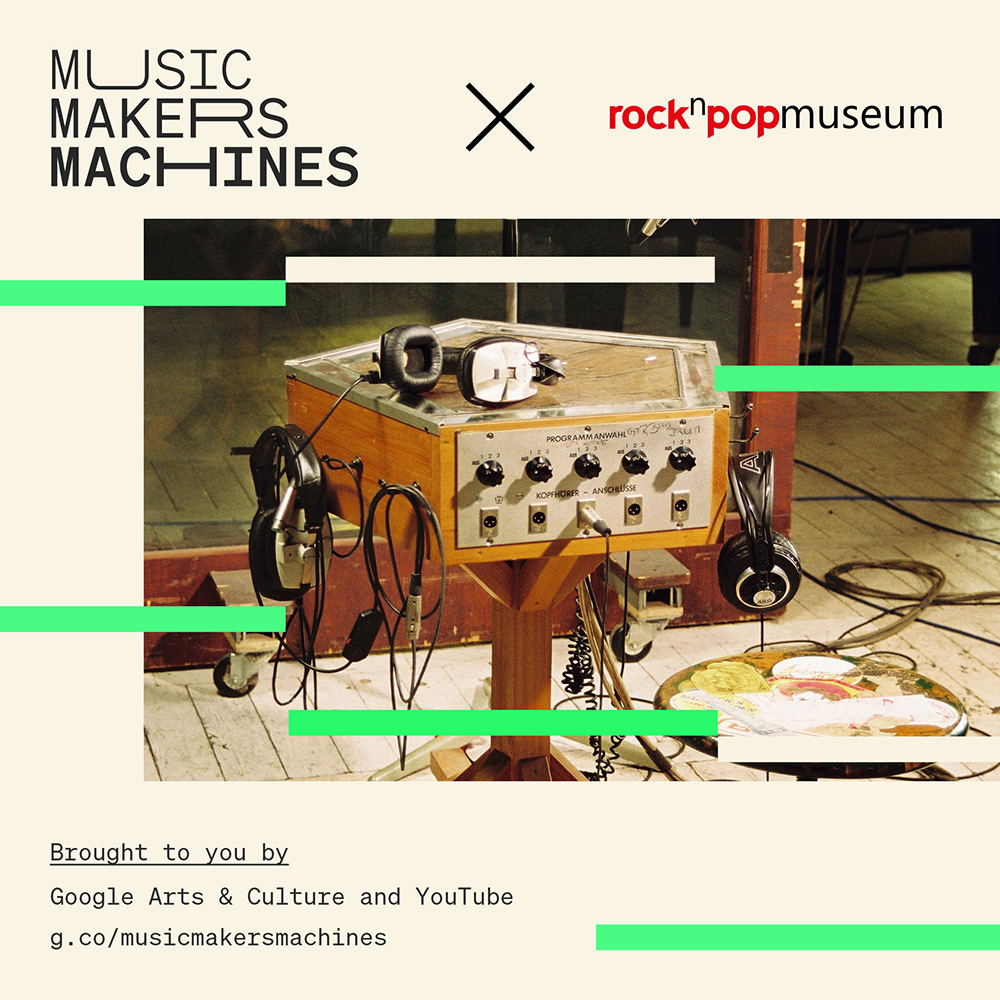

The remarkable thing, however, was the structure of the “Inner Vision Studio” as it was initially named: This was because there was no separation between the control room and recording room. The 8-channel mixing console used to create CAN's early albums stood in the middle of the room. This console was later preserved. Until the mid-1970s, the band's technical equipment remained modest, leaving few options for correcting errors or elaborate miking set-ups. Looking back, the band members believed that their sound was influenced both by the special ambience of the studio and its technical limitations.

In 1978, after CAN split up, René Tinner took over the studio. He had worked in Weilerswist before and, following a brief stint with another studio, he came back with an idea: His plan was to turn the experimental space into a commercial music studio. Things really started happening for the former cinema, which had been renamed CAN-Studio, after a first big hit: Joachim Witt scored a major success with his album “Silberblick”, which was recorded there. The proceeds from this production went into purchasing a CS-V mixing console, which is the centrepiece of the collection at the rock'n'popmuseum.

Then came national and international acts produced by Tinner who paid tribute to the unique atmosphere of the space. Alongside Fury in the Slaughterhouse and Double, Tinner’s biggest production was probably Marius Müller-Westernhagen. His successful album Halleluja was produced in the CAN studio. Just like CAN’s recordings of its jams, the live experience of the band also took centre stage here.

Over the years, the studio had become a professional powerhouse: 24-track machines, a Hammond organ, dozens of synthesisers from analogue to digital. At this peak of its technical capabilities, the studio relocated to the rock'n'popmuseum in the mid-2000s, where you can explore it in the museum’s basement.

Wir nutzen temporäre Session-Cookies auf unserer Webseite. Ein Session-Cookie speichert lediglich Informationen, die Onlineaktivitäten einer einzelnen Browser-Sitzung zuordnen. Die Session-Cookies werden beim Schließen des Browsers wieder gelöscht. Durch die weitere Nutzung der Webseite stimmen Sie der Verwendung dieser technisch notwendigen Cookies zu.